Toward the end of the trip, Jamie was uncharacteristically in a daze, staring up at the magnificent dome of St. Peter’s.

“I think I am the patron saint of mediocrity,” he mused, paraphrasing the famously self-critical line from the movie Amadeus. He was dumbstruck by Michelangelo. How could one person produce so many masterpieces and leave such a staggering legacy of architecture, art, poetry and sculpture?

Jamie is now a professor at the Stuckeman School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture at Penn State University. Much of his academic research is focused on Michelangelo’s design process and architecture, and he is currently writing a book on the topic for a prestigious academic publisher. He became fascinated by how Michelangelo used his incredible drawing skills to rapidly develop design ideas. Indeed, free-hand drawing and sketching were central to Michelangelo’s method of design.

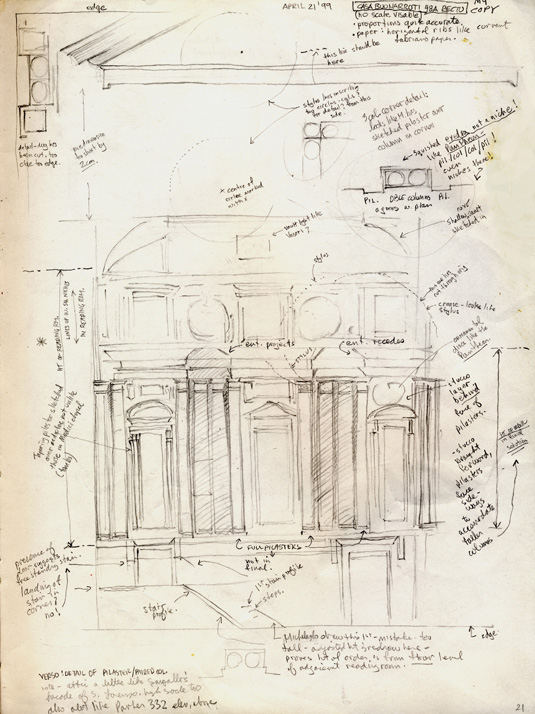

Copy of Casa Buonarroti 48A recto: Jamie's sketchbook facsimile of an important design development sketch by Michelangelo, for his penultimate design for the Laurentian Library vestibule, Florence

Copy of Casa Buonarroti 48A recto: Jamie's sketchbook facsimile of an important design development sketch by Michelangelo, for his penultimate design for the Laurentian Library vestibule, Florence

Jamie developed a unique research methodology that combines his background and skills in drawing, design and architectural history, providing him a unique perspective from which to study Michelangelo.

At Pivot, we knew we had much to learn from Jamie in order to better understand and be inspired by Michelangelo, the great Italian Renaissance master. Below is an abridged “sketch” of our chat with Jamie.

Michelangelo, the man

Jamie argues that one of the greatest works of art by Michelangelo was Michelangelo himself.

According to his biographers, Michelangelo did his best to eliminate evidence of his labours by having his assistants periodically burn his design development sketches and drawings. He wanted us to believe that all these masterpieces in sculpture, painting and architecture, already exisited, fully formed in his mind.

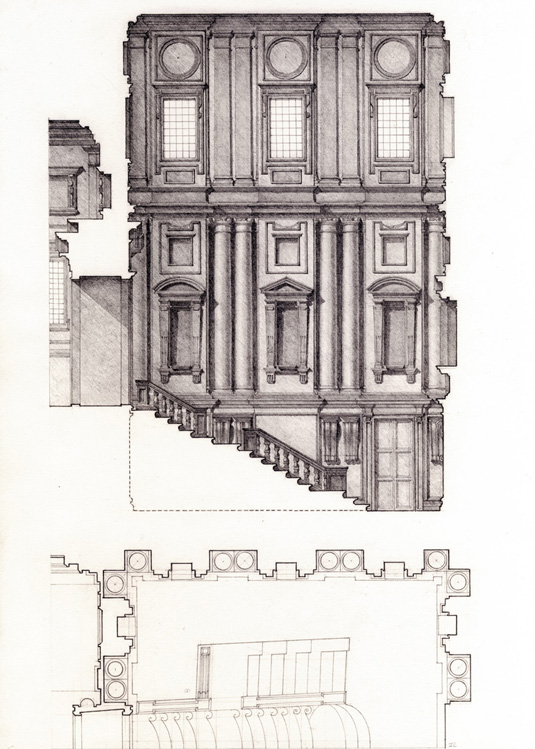

Hypothetical reconstruction of Michelangelo's penultimate design for the laurentian Library vestibule, sectional "worm's eye" isometric (Cooper)

Hypothetical reconstruction of Michelangelo's penultimate design for the laurentian Library vestibule, sectional "worm's eye" isometric (Cooper)

As is the case with many great geniuses and artists, the truth of his laborious creative process contradicts the common romantic vision of the lofty god-like genius. However, it appears his strategy worked, since both during and after his lifetime he was commonly referred to as “Il Divino”.

Michelangelo’s Revolutionary Approach

Michelangelo examined a wide range of surviving ancient Roman Classical works of architecture as well as more recent Renaisance examples created by his predecessors and contempories. In doing so, it is apparent that he came to realize that the classical language of architecture and its vocabulary of forms held an almost limitless degree of creative potential — much more so than had been understood by the preceeding generation of Renaisiance architects. A good analogy of this would be poetry. It’s almost like Michelangelo has a finite number of words, but what he’s changing is the syntax: the ways in which the words are combined to create new compositions.

He took liberties with classical elements and rules, but always with great respect.

Michelangelo’s Process

Michelangelo’s process of design is obviously dependent on good drawing skills. However, as evidenced in his own early sketches, they did not need to be, nor did he intend for them to be beautiful. Michelangelo was of course capable of creating breathtakingly beautiful drawings. But, in his process, he wasn’t aiming for beauty. This was a very practical approach to architecture in which he started with the most basic, fundamental problem, and quickly developed a number of ideas and solutions. In every case, there were what many would consider suffocating constraints and major practical issues to be solved.

Interestingly, Michelangelo was not straightjacketed by these constraints; he was inspired by them.

Laurentian Library Vestibule Section (Cooper): graphite rendered partial plan and cross-section of the famous Laurentian Library Vestibule and staircase (compare to Casa Buonarroti 48A recto)

Laurentian Library Vestibule Section (Cooper): graphite rendered partial plan and cross-section of the famous Laurentian Library Vestibule and staircase (compare to Casa Buonarroti 48A recto)

Today, architects want to have a clean slate and they think of architecture as sculpture where it’s entirely a means of self expression. It’s not. It’s a social art; people occupy space. You walk by a sculpture and ignore it if you don’t like it. You can’t ignore a building if you’re working in it, you live in it, or you’re navigating through it. Michelangelo thought of the city itself as one total work of art and that his architecture would be either contributing to it or taking away from it. So, he’s thinking on a highly macro scale and working his way right down to the smallest details.

Lessons to be Learned from Michelangelo’s Process

Nowadays there’s this pathological desire and striving need to be original. When it comes down to it, no one is truly original, there’s always lessons that can be learned from the past.

Jamie’s advisor at U.Va. often says, “Every building is made from parts of other buildings, and if anyone tells you otherwise, they’re not being honest.” Indeed, even the great modernist pioneer Mies van der Rohe stated, towards the end of his career, “We do not have to invent a new architecture every Monday morning.”

On-site sketches of a typical bay of the Palazzo dei Conservatori at the Campidoglio, and interior elevation of the Chapel of the King of France, south transept, St. Peter's. (Cooper)

On-site sketches of a typical bay of the Palazzo dei Conservatori at the Campidoglio, and interior elevation of the Chapel of the King of France, south transept, St. Peter's. (Cooper)

Michelangelo always kept himself busy — he was an obsessive workaholic and a great multitasker. When he got bored with one project he would flip to another one, and usually had several projects in a variety of media on the go at once. His process of design in all of the arts was similar, and it would seem that they inevitably fed off of one another.

Michelangelo’s manic energy and creative drive leads us to believe that he was a perfectionist. He left behind numerous unfinished projects. It would appear that for him, the design process was never ending; it was practially impossible for him to live up to his own standards, to know when to stop, and bring a project to a close.

Through our conversation with Jaime, we believe that Michelangelo, in his own way, understood that his early ideas, and his initial sketches, were essential steps in an iterative evolution that would lead to the final design.